In 1989, rock music inspired a revolution, and that can give us hope for today – The Dallas Morning News

In 1989, rock music inspired a revolution, and that can give us hope for today The Dallas Morning News

The Dallas Morning News is publishing a multi-part series on important issues for voters to consider as they choose a president this year. This column is part of the final installment of our What’s at Stake series, which focuses on optimism. Find the full series here.

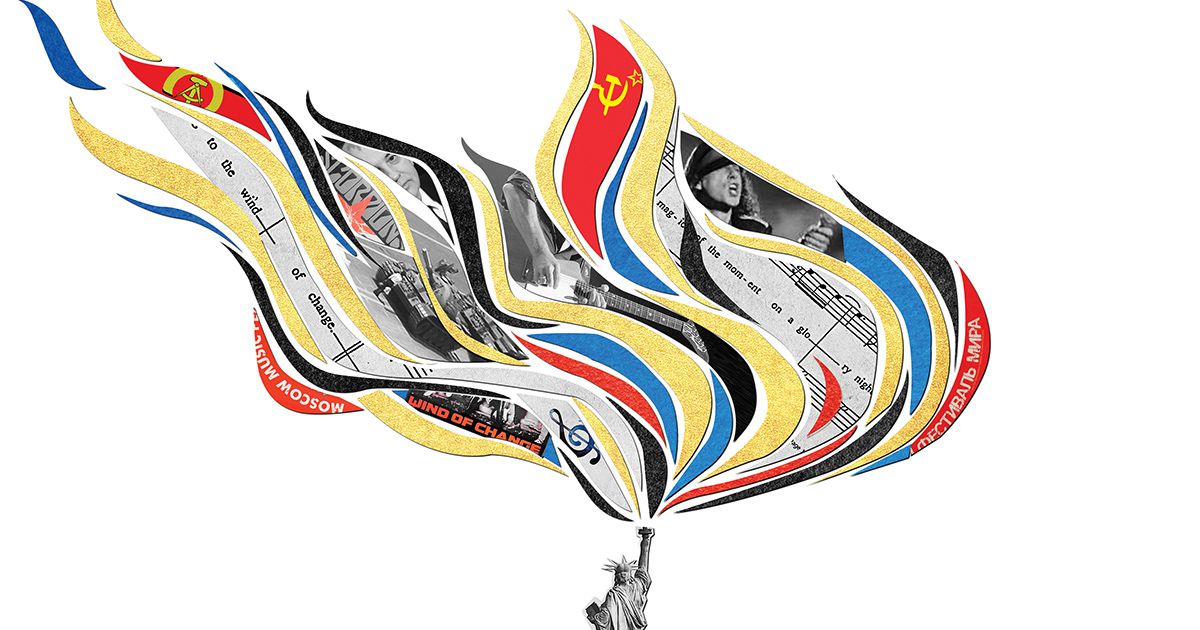

One of the most cynical souvenirs of 2020 is a podcast called “Wind of Change,” which spreads a conspiracy theory that the Scorpions song by that name, the anthem of the Eastern European revolutions that broke the Soviet Union, was written by the CIA.

The podcast creator, Patrick Radden Keefe of The New Yorker, sounds like the grade school punk who told you the tooth fairy isn’t real. Only he offers zero evidence, and his podcast marks a low point of America’s faith in itself. Not because the CIA would never use pop culture to influence foreign nations, of course it has. But because this conspiracy theory erodes not just American faith in its institutions, but American faith in its values.

If we stop believing that the American idea of freedom, on its own merit, can spread to people living under oppressive governments, and can do so via our best cultural creations such as rock and roll, then we stop believing in America. This year is a good time to recall that American values and culture were so infectious in the last century, that music helped inspire a generation of young people to risk their lives to demand that the Soviet Union change. And it did.

In 2020, we walk around with devices in our pockets that can call up just about any song ever recorded and play it for us immediately. The contrast to the 20th century Soviet Union is glaring. The USSR censored Western music, movies, books and other products, so people living in Eastern Bloc countries listened generally to classical music, or regional folk and pop songs. More Lawrence Welk than Elvis Presley.

But an underground music culture grew, with young people risking fines or jail time to get their hands on albums from friends in the West and use ingenious methods to copy and distribute the music. The West German band the Scorpions didn’t play political music before 1989; they just wanted to “Rock You Like a Hurricane.” But the act of listening to their music in the Eastern Bloc was political.

Klaus Meine, the leader of the Scorpions, is a Baby Boomer from Hannover who, according to an interview with him in the podcast, is a true believer in the power of rock and roll to change the world. He is not unlike many West Germans of his generation, who grew up watching their parents work to rebuild their country and grapple with the shame of the Nazi era. British occupiers in Hannover worked with Americans to help implement their vision of human freedom in Germany, and it must have looked pretty good compared with what was happening in the Soviet zone. And anyway, the radio played American and British rock and roll.

As the Scorpions became famous, Meine was aware of the band’s growing popularity in Eastern Europe, and the band was slowly allowed to do occasional concerts in Eastern cities. He saw what heavy metal meant to young people behind the Iron Curtain. And when the Scorpions headlined the Moscow Music Peace Festival in 1989 that featured for the first time a line-up of American bands, including Mötley Crüe, Bon Jovi and Skid Row, Meine was inspired to write “Wind of Change.”

Podcaster Keefe wonders how Meine could have possibly known the wall was about to come down three months after he wrote the song. (And Keefe points to the timing as evidence that the CIA might have been behind the song.) No, Meine didn’t know; nobody knew. The Berlin Wall opened on Nov. 9, 1989, because a member of the East German Politburo botched a statement at a press conference on live television, and the authorities could do nothing to stop the joyful crowds.

But anyone who had been observing youth culture as Meine had could see the street protests growing as more people gained the courage to publicly demand freedom. And everyone following the news could see Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev slowly easing restrictions. Mötley Crüe played Moscow, for heaven’s sake.

The Scorpions recorded “Wind of Change” in 1990 and the song was released as a single the following year, becoming, according to Rolling Stone, one of the best-selling singles in history, hitting No. 1 on the music charts across Europe and No. 4 in the U.S. The Scorpions went on to record versions in Russian and Spanish.

In the podcast, Keefe argues, correctly, that “Wind of Change” may have been the most important rock song ever released, but the song doesn’t get a lot of play in the U.S. anymore. Perhaps that’s because the lyrics are a jumble of clichés put together oddly. And here is overwhelming evidence that this song was written by a West German with very strong English language skills, who was familiar with idioms and clichés, but didn’t have the native speaker’s sense for their typical meaning.

The chorus:

Take me to the magic of the moment

On a glory night

Where the children of tomorrow share their dreams (share their dreams)

With you and me

Take me to the magic of the moment

On a glory night (the glory night)

Where the children of tomorrow dream away (dream away)

In the wind of change (the wind of change)

Would an American songwriter working for the CIA write about the “magic of the moment” as a place you could be taken to? Would an American write “glory night,” or “glorious night?” Would a native English speaker equate dreams of ambition with the term “dream away,” meaning to fantasize? No. But a German rocker might. And the cliché jumble has the effect of making a different meaning of the idioms that somehow beautifully captures the wind of change that blew through the Soviet Union.

The 20th century effectively ended in 1989, with a wave of revolutions (and, in the case of Tiananmen Square, the government obliteration of a revolution) and the birth of the internet. The year set the stage for the next century, which for Americans would effectively begin on Sept. 11, 2001.

Now it’s our turn, 21st century Americans, to take inspiration from the youth of 1989 Eastern Europe. Rather than cynically theorize that our intelligence agents manipulated millions with an earworm, we can believe that, in fact, rock and roll really did change the world. If we want America to continue, we must risk optimism that our domestic conflicts are not the intended result of some government agency conspiracy, but the disagreements of free people undertaking the painful work of securing the blessings of liberty.

Elizabeth Souder is the Sunday Opinion and commentary editor and a member of The Dallas Morning News editorial board.