The Wild Story of Creem, Once ‘America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine’ – The New York Times

The Wild Story of Creem, Once ‘America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine’ The New York Times

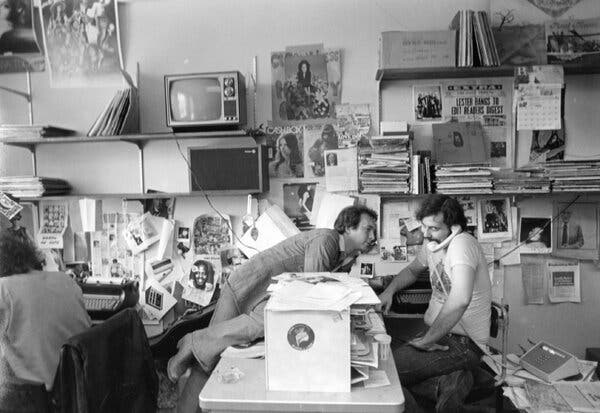

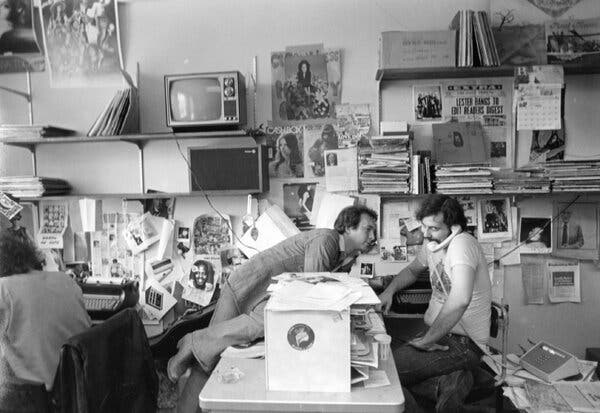

On Jaan Uhelszki’s first day at Creem magazine in October 1970, she met a fellow new hire: Lester Bangs, a freelance writer freshly arrived from California to fill the post of record reviews editor. His plaid three-piece suit made him look like an awkward substitute teacher, she thought, and certainly out of place among the hippies and would-be revolutionaries using the publication’s decrepit Detroit office as a crash pad.

Uhelszki, still a teenager, was majoring in journalism at nearby Wayne State University, and had been sent to the fledgling rock magazine by editors at the student newspaper. “They said with a sneer, ‘We can’t publish you, you don’t have any clips, but Creem will publish anybody, why don’t you go walk down the street,’” Uhelszki said in a phone interview. “So my first clips were Creem. I started at the top.”

She’d arrived at the headquarters of “America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine,” as Creem’s front covers would soon proclaim. What began as an underground newspaper soon evolved under Bangs, the editor Dave Marsh and the publisher Barry Kramer into a boisterous, irreverent, boundary-smashing monthly that was equal parts profound and profane. During his half-decade at Creem, Bangs would publish many of the pharmaceutically fueled exegeses that made him “America’s greatest rock critic” — including his epic three-part interview with his hero/nemesis Lou Reed. By 1976, it had a circulation of over 210,000, second only to Rolling Stone.

The magazine’s roller-coaster arc and its lasting impact on the culture is the subject of a spirited new documentary directed by Scott Crawford, “Creem: America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine,” which Uhelszki co-wrote and helped produce. The film opens Friday for virtual cinema and limited theatrical release, and comes to VOD on Aug. 28.

As a teenager, Crawford bought old issues of Creem from used bookstores near his home outside Washington, D.C. His first film was “Salad Days,” a 2014 documentary about the city’s hardcore punk scene.

“I was aware of the personalities involved,” he said of the Creem crew. “I’d heard stories over the years of their fights, literal fistfights, so I knew that this would make for a hell of a film because in addition to how much they contributed to music journalism, a lot of the writers were just as interesting as the artists that they covered.”

The documentary traces how Creem’s high-intensity environment mirrored that of the late 1960s Detroit rock scene, which was centered around the heavy guitar assault of bands like the MC5, the Stooges and Alice Cooper. Barry Kramer, a working-class Jewish kid with a chip on his shoulder and a volatile temper, was a key local figure: He owned the record store-cum-head shops Mixed Media and Full Circle.

“I liked Barry a great deal, and in fact I wanted him to manage the MC5,” the band’s guitarist Wayne Kramer, who is not a relation, said in a phone interview. (He also handled original music for the film.) “He had a vision and saw ways that this emerging counterculture could be monetized.”

The original idea for Creem came from a clerk at Mixed Media, Tony Reay, who persuaded Barry Kramer to put $1,200 into the venture, which began in March 1969. When the cartoonist Robert Crumb wandered into Mixed Media in need of cash, Reay offered him $50 to draw the cover of issue No. 2. Crumb’s illustration included an anthropomorphized bottle of cream exclaiming “Boy Howdy!,” which became the magazine’s mascot and catchphrase.

Reay soon departed over creative differences, and the magazine briefly took on a more political flavor, thanks to Marsh, a 19-year-old Wayne State student. The arrival of Bangs in 1970 was explosive.

“They both had different ideas of what Creem should be,” Uhelszki said. “Lester just saw us as bozo provocateurs, and David wanted it to be a more political magazine and saw us as foot soldiers of the counterculture.”

In 1971, a robbery at the Cass Corridor offices spurred Barry Kramer to move the magazine to a 120-acre farm in the rural suburb Walled Lake. The staff lived there communally for two years: sharing three rooms and one bathroom, working and socializing around the clock amid a menagerie of dogs, cats and horses. In the film, Uhelszki reveals that a trip to the bathroom in the middle of the night meant possibly encountering Kramer and getting a lecture about copy while half-awake, and that Marsh once deposited wayward excrement from Bangs’s dog onto Bangs’s typewriter.

“We had rolled out into the driveway,” Marsh recalls of the ensuing fistfight, “and I got my head smacked into an open car door. That’s OK, he wasn’t trying to hurt me, he was just trying to win.”

In 1973, the commune experiment ended and Creem relocated into a proper office in Birmingham, one of Detroit’s toniest suburbs. Still, the city’s scrappy, underdog spirit remained a crucial element of the magazine’s aesthetic. “I don’t think it could have existed anywhere else,” Alice Cooper said in a phone interview. “In New York it would have been more sophisticated; in L.A. it would have been a lot slicker. Detroit was the perfect place for it, because it was somewhere between a teen magazine and Mad magazine and a hard rock magazine.”

Rolling Stone felt comparatively stuffy, preoccupied with movies and politics and reluctant to cover loud and snotty subcultural movements like punk and metal, whereas Creem’s pages first coined those genre’s names: “punk rock” by Marsh, about ? and the Mysterians, and “heavy metal” by Mike Saunders, about Sir Lord Baltimore, both in the May 1971 issue.

The reader mail page provided a ribald frisson between the writers and their audience. The most infamous exchange came in 1977, after the writer Rick Johnson opened his review of the second Runaways album, “Queens of Noise,” by declaring “These bitches suck. That’s all there is to it.” An infuriated Joan Jett visited the Creem office to confront him; when told Johnson wasn’t there, she settled the score in the letters column.

Musicians were not only the subject of the publication, they were often its authors; Patti Smith and Lenny Kaye became contributors. And Creem writers sometimes scaled the fourth wall themselves. The J. Geils Band singer Peter Wolf invited Bangs to “play” his typewriter onstage; Uhelszki was gussied up by Kiss in full “Hotter Than Hell” makeup and played (unplugged) guitar onstage for her August 1975 story “I Dreamed I Was Onstage With Kiss in My Maidenform Bra.”

Subversive humor was the Creem lingua franca. Snarky photo captions and regular features like the Creem Dreems (tongue-in-cheek pinups of artists like Debbie Harry and Bebe Buell) were clearly intended for — and driven by — adolescent hormones, but the magazine provided opportunities for women writers like Roberta Cruger, Cynthia Dagnal, Lisa Robinson and Penny Valentine at a time when the music industry was intensely misogynist. “We had so many women who were empowered and were editors at the time,” Susan Whitall says in the film. “When I came in, Jaan mentored me, and then I mentored other women.”

Still, seen through today’s eyes, some of the old Creem content can seem puerile, even offensive. The casual sexism and homophobia is sadly typical of its time, and racial sensitivity was nonexistent. Yet its anarchic attitude and early embrace of new wave and punk inspired future musicians like Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore, Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament and Metallica’s Kirk Hammett, who all appear in the film. In one scene, R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe recalls the first time he ever saw a copy of Creem, during detention in high school, and being mesmerized by a photo of Patti Smith.

“From that moment forward my entire life shifted and changed dramatically,” Stipe says. “I was like, what world is this? Most people want to fit in somewhere. Because of my otherness, because of my queerness, I was trying to find that gang. I wasn’t going to find it in my high school. I found it in Creem magazine.”

Uhelszki said making the documentary revealed that musicians devoted to the magazine were empowered by what they read. “The people who made the magazine, we thought we were equals to the bands in the early years,” she said. “Rock stars were just like us but they had better clothes than we did.”

As the 1970s expired, all the hard partying took a toll. Bangs, who had departed Detroit and Creem in 1976 for New York, died of an accidental painkiller overdose in 1982. After a long spiral of drinking and drugging, Barry Kramer overdosed on nitrous oxide in 1981. He left the magazine to his 4-year-old son, JJ, who was listed on the masthead as the chairman of the board.

With the magazine heavily in debt, Barry Kramer’s former wife, Connie, sold Creem to an investor in 1986 who moved it to Los Angeles. The company changed ownership several times before the magazine finally ceased publication in 1989. Considerable litigation lingered into the 2000s, until the Creem brand was acquired by JJ Kramer’s company in 2017.

For JJ Kramer, also one of the movie’s producers, the documentary project was more than a film; it was an opportunity to discover the father he never knew. “Before we did the movie, I think I can remember actually hearing his voice maybe once or twice,” he said in a phone interview. “That’s why the film was such an incredible experience for me, just getting to know who he was as a person — the good, the bad, the ugly and the crazy — which in turn taught me a lot about myself as well.”

An intellectual-property lawyer, JJ Kramer spent 20 years gathering the rights to the old material, and is eager to make the magazine’s archive available for a new generation. To coincide with the film’s release, a limited-edition best-of-Creem issue will be available on newsstands on Nov. 1, and additional print editions are being considered, as well as a TV show.

“I view the documentary as very much the beginning, not the end,” he said. “We’re all looking for something to capture our attention and our passion, so to me that feels like a really strong signal that the world might need Creem more than ever.”